Introduction

We describe a clinical case where a pregnant woman with

twin gestation was given Tranexamic Acid (TXA) after delivery of

her two neonates but was found to have a third fetus during placenta removal. Tranexamic acid is an antifibrinolytic agent that

has been widely studied for its potential in reducing Postpartum Hemorrhage (PPH) [1]. Postpartum hemorrhage, defined

as bleeding ≥500 mL in the first 24 hours after delivery, is responsible for 25% of all maternal deaths worldwide [1]. Despite

advances in obstetric care, PPH remains a significant concern.

Several studies, including the WOMAN Randomized Controlled

Trial (RCT), have investigated the effects of TXA in women with

PPH [2]. Results demonstrate that the use of TXA significantly

reduces maternal death due to bleeding, without any increase

in maternal adverse events. These benefits were particularly

pronounced when TXA was administered within three hours of

birth. Few studies, however, have thoroughly investigated the

effects of TXA on neonates in utero.

Drugs that are lipid soluble, smaller (<500 Da), non-protein

bound, and have a low ionized fraction have greater placental

transfer. Tranexamic acid is a class B pregnancy drug that can

pass through the placental barrier, with its concentration in

cord blood matching that in maternal blood. Other classes of

drugs known to cross the placenta include opiates, benzodiazepines, local anesthetics, beta blockers and barbiturates. When

considering the administration of any medication during pregnancy or labor, it is important to weigh the potential benefits

against the risks to both mother and fetus.

Case presentation

A 37-year-old G3P1101 woman at 34 weeks and 6 days of

dichorionic twin gestation dated by fetal ultrasound with a history of preeclampsia without severe features, Wolff-Parkinson

White syndrome treated with ablation, endometriosis, and

rheumatoid arthritis on hydroxychloroquine presented to our

Labor and Delivery floor. In triage, her systolic blood pressure was in the 150s and diastolic pressures were in the 100s. She

also reported daily headaches for the past 4 months and worsened lower extremity edema. Her Aspartate Aminotransferase

level (AST) was elevated to 45 units/L, and her protein to creatinine ratio increased to 3 from 0.89. Given the worsening features of her preeclampsia, magnesium was started and a plan

for repeat Cesarean Delivery (CD) with tubal sterilization was

established.

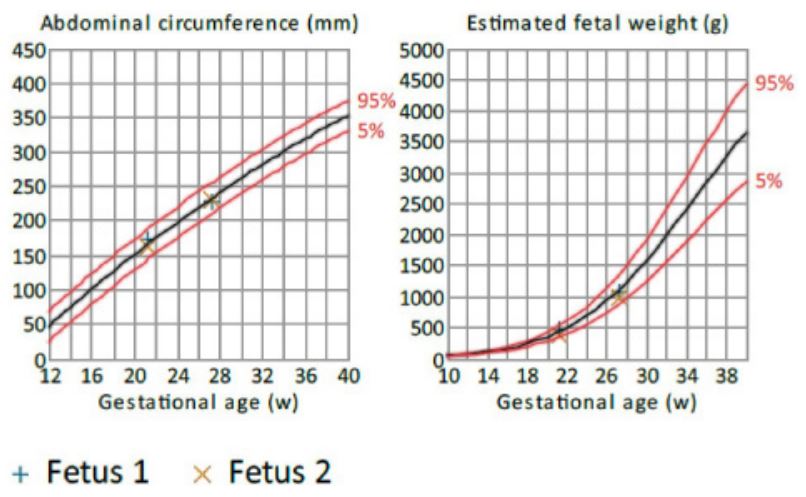

The patient’s most recent fetal ultrasound demonstrated dichorionic diamniotic twin gestation at 14 weeks. Growth charts

of the two known fetuses were within normal limits based on

transabdominal ultrasound at 27 weeks (Figure 1). Prior to delivery, a combined spinal epidural was placed. Amniotomies for

the first and second neonate were performed for clear fluid.

Following their deliveries, an attempt was made to deliver the

placentas. With gentle traction on the umbilical cords, a bulging bag was noted at the hysterotomy. Thought to be a residual

membrane sac, the bag was ruptured, revealing the back and

shoulders of the third neonate. Prior to this third delivery, oxytocin and tranexamic acid had been started for PPH. The patient’s blood loss was estimated to be 1.5 L. After being told the

news, the patient described the experience as a “miracle” and

is happy with the arrival of her third newborn.

Discussion

The effect of TXA on neonatal outcomes has been sparsely

studied. Tranexamic acid may cause serious side effects in neonates before cord clamping [3-5]. Several published studies and

case reports have described fetal and neonatal functional issues

such as low Apgar score, neonatal sepsis, cephalohematoma,

low birth weight, and preterm birth in fetuses and infants exposed to TXA in utero [6]. However, no RCTs examining TXA

administration for women undergoing CD have clearly demonstrated that these risks are associated with TXA. Tetruashvili et

al. 2007 used TXA to stop bleeding in women with recurrent

and threatened miscarriages [7].Although two neonates passed

away, their deaths were attributed to the severe bleeding complications from placental abruption, rather than the administration of TXA. In another RCT investigating TXA for reducing intraoperative blood loss after high-risk CD, there were no significant

differences in neonatal APGAR scores or NICU admission rates

[8]. Additionally, the WOMAN trial did not find any significant

difference in neonatal deaths, stillbirths, or other adverse neonatal outcomes [2].

While evidence suggests TXA does not appear to be associated with increased risks to neonates, robust RCTs are still lacking

[2,7,8]. Plus, in this case of a third undetected fetus, additional

medications other than TXA were administered around the time

of delivery including fentanyl, acetaminophen, ropivacaine,

phenylephrine and oxytocin, all of which cross the placenta.

Physiologic changes during pregnancy alter maternal pharmacokinetics, which in turn affect the amount of drug reaching

the placenta and fetus. One study found no increased risk of

thrombosis or seizures in neonates administered TXA at these

doses [9].Nonetheless, even if TXA and other drugs are safe in

neonates, we do not know the impact of delivering postpartum

dosages of medications to an undelivered fetus.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest: None.

Source of funding:: None.

Contributor roles: Dhanesh D. Binda: conceptualization, investigation, reviewing, editing, and writing.

Rachel Barkley: Conceptualization, investigation, reviewing, editing, and writing.

Maxwell Baker: Conceptualization, investigation, reviewing, editing, and writing.

Rachel Achu-Lopes: Conceptualization, supervision, reviewing, and editing.

Ala Nozari: Conceptualization, supervision, reviewing, and editing.

Shooka Esmaeeli: Conceptualization, supervision, reviewing, and editing.

References

- Sentilhes L, Lasocki S, Ducloy-Bouthors AS, et al. Tranexamic acid for the prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. Br J Anaesth. 2015; 114(4): 576-587. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu448

- WOMAN Trial Collaborators. Effect of early tranexamic acid administration on mortality, hysterectomy, and other morbidities in women with post-partum haemorrhage (WOMAN): an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial [published correction appears in Lancet. 2017; 389(10084): 2105-2116. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30638-4.

- Seguin N, Visintini S, Muldoon KA, Walker M. Use of tranexamic acid (TXA) to reduce preterm birth and other adverse obstetrical outcomes among pregnant individuals with placenta previa: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 2023; 13(3): e068892. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068892

- Peitsidis P, Kadir RA. Antifibrinolytic therapy with tranexamic acid in pregnancy and postpartum. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011; 12(4): 503-516. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2011.545818

- Walzman M, Bonnar J. Effects of tranexamic acid on the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems in pregnancy complicated by placental bleeding. Arch Toxicol Suppl. 1982; 5: 214-220. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-68511-8_39

- Pfizer Canada. Product monograph including patient medication information: cyklokapron tranexamic acid [Pfizer Canada]. 2021. Available: https: //www.pfizer.ca/files/CYKLOKAPRON_PM_E_254356_25-Nov-2021.pdf.

- Tetruashvili NK. Hemostatic therapy for hemorrhages during first and second trimesters. Anesteziol Reanimatol. 2007; (6): 46-48.

- Shalaby MA, Maged AM, Al-Asmar A, El Mahy M, Al-Mohamady M, et al. Safety and efficacy of preoperative tranexamic acid in reducing intraoperative and postoperative blood loss in highrisk women undergoing cesarean delivery: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022; 22(1): 201. doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-04530-4

- Wesley MC, Pereira LM, Scharp LA, Emani SM, McGowan FX, et al. Pharmacokinetics of tranexamic acid in neonates, infants, and children undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesthesiology. 2015; 122(4): 746-58. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000570. PMID: 25585004.