Introduction

In this case report we described a Mullerian anomaly associated with renal agenesia in a syndromic framework of HerlynWerner-Wunderlich syndrome. We underline the need of multidisciplinary counselling for those complex cases where the

genetician, gynecologist, urologist should work together. The

uniqueness of our case lies in the presence of a slightly symptomatic hematometra measuring 11 cm by 5 cm. This condition

is noteworthy because it was initially misdiagnosed as an endometrial cyst on an MRI. The initial misdiagnosis highlights the

challenge and importance of accurate imaging and diagnosis

in such cases. Despite the hematometra’s significant size, the

patient exhibited only mild symptoms, adding another layer of

complexity to the diagnosis and subsequent treatment plan.

Case report

We report the case of a 15-years-old woman who presented

to our emergency room compelling for abdominal pain with

a location in lower right iliac fossa. Her menarche was at age

of 13; her menstrual period was reported irregular with oligo\

amenorrhoic menstruations with dismenorrea. She had congenital right renal agenesia and no family history for neoplastic

pathologies. An abdominal ultrasound executed in ER revealed

a dysomogeneous pelvic mass without vascular sign on the

right side, near the adnexal area, suspect for endometirosic

cyst. Near the cyst it was the evidence of a tubular neoformation of about 11 cm x 5 cm, suspect for sactosalpinx. No free

fluid in the Douglas. The patient was hospitalized and subjected

to full blood assessment, EKC, determination of oncomarkers.

The oncomarkers AFP, CEA, CA15.3, CA19.9 were negative with

a slight augmentation of CA125 of 36,7 U/mL (Cutoff: 0-35 U/

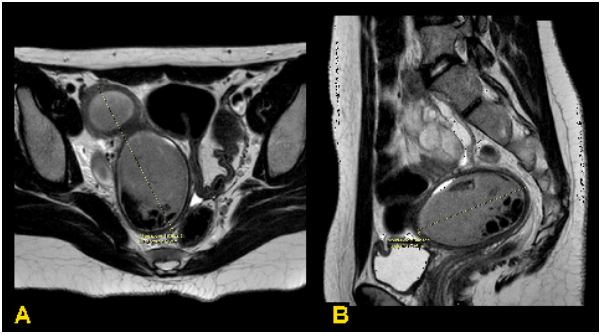

mL). Blood test and EKG was normal. Abdominal MRI showed

a pelvic, paramedian right abdomino-pelvic mass of about 18

cm, with hourglass shape and dishomogeneous contrast enhancement, suspected for endometrioma, that compressed

and dislocated the uterus and the sigmoid ansa to the left (Figure 1). The patient was subjected to hysteroscopy. Underwent

general anestesia the patient went in the surgical room for the

intervention. We performed a hysteroscopy without speculum

with a 3.5 mm minihysteroscope (Versascope, Gynecare, Ethicon, Sommerville, NJ, U.S.A.) with saline solution as a distending medium. The vaginal space appeared narrowed because of

the bulging hemivagina; we highlithed the presence of a right

uterine cervix on the right and a vaginal septum on the left.

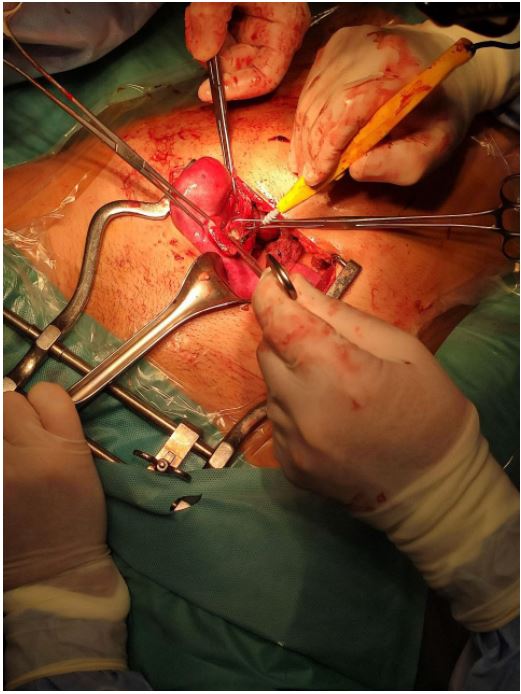

The vaginal septum was punctured under transabdominal ultrasound guidance, but no material was drained. We converted

the surgical intervention via laparotomy, revealing the presence

of a uterus didelphys with the right uterus increased in volume

and consistency compatible with hematometra and normal left

uterus (Figure 2). The distal portion of the right salpinx showed

multiple endometriotic implants. She had one vagina and a

second cervix on the right side not connecting with the uterine cavity for the presence of a septum. She had a vaginal plastic

surgery and hematometra drainage. This Mullerian anomaly associated with congenital unilateral renal agenesis suggests the

presence of an Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich syndrome. The postoperative period was uneventhful and the hospital discharge

was in III post-operative days. The hystologic exam was negative

for neoplasy.

Table 1: Main genes implicated in congenital syndromes involved in mullerian anomalies (Modified and adapted from [16]).

| Syndrome |

Inheritation |

Etiology |

Reproductive Anomaly |

Other Findings |

| Acro-renal mandibular |

AR |

/ |

DU |

Diaphragmatic hernia, , |

| Antley-Bixler |

AD |

FGFR2 POR (AR) |

VA |

Choanal atresia, |

| Apert |

AD |

FGFR2 |

VA, BU |

Cardiac disease |

| Cloacal exstrophy |

/ |

/ |

Incomplete mullerian

fusion |

|

Female pseudohermaphroditism with renal and

gastrointestinal anomalies |

/ |

/ |

DU Genital ambiguity,

UA |

KA |

Female pseudohermaphroditism, renal and gas-

trointestinal anomalies |

/ |

/ |

UA, Genital ambiguity, |

KA, Gastrointestinal anomalies, |

| Fraser |

AR |

FRAS1, FREM2, GRIP1 |

VA, BU |

KA, Mental retardation |

| Meckel |

AR |

MSK1, TMEM216, TMEM67,

CEP290, RPGRIP1L, CC2D2A |

BU Male

pseudohermaphroditism |

Dysplastic polycystic kidneys,

encephalocele |

| Mosaic trisomy 7 |

/ |

Chromosomal |

UA |

Cystic kidneys, |

| MURCS association |

/ |

/ |

VA, UA |

KA |

| Pallister Hall |

AD |

GLI3 |

VA |

cardiac defects |

| Roberts |

AR |

ESCO2 |

BU, UA , VA |

Cardiac defects |

| Roberts |

AR |

ESCO2 |

UA and VA |

Tetraphocomelia,, cardiac defects |

| Rüdiger |

AR |

/ |

BU |

ureteral stenosis, mental retardation |

| Urogenital adysplasia |

/ |

/ |

Unicornuate or BU |

KA |

Note: AD: Autosomic Dominant; AR: Autosomic Recessive; VA: Vaginal Atresia; BU: Bicornuate Uterus; UA: Uterus Agenesia; DU: Didelphys

Uterus; KA: Kidney Anomalies; KA: kidney Agenesia.

Discussion

Congenital Uterine Anomalies (CUA) result from abnormal

formation, fusion or resorption of the Müllerian ducts during

fetal life [1], that are usually detected incidentally during fertility investigations: CUA’s could be asymptomatic and most

women with uterine anomalies could have a normal reproductive outcome; however some women may experience adverse

reproductive outcome with an increased rate of miscarriage,

preterm delivery and other adverse fetal outcomes [2-8]. In

the general population the incidence of CUA is about 7%, with

a prevalence of arcuate (68%) and septate uterus (27%) and a

rarity of bicornuate (4%) and didelphys (0.4 %) uterus. The incidence of CUE in infertile population is almost identical to general population, with a predominance of septate uterus (46%)

and arcuate uterus (25%). Patients diagnosed with multiple

miscarriages have a higher prevalence of CUA, accounting for

about 17% of cases, with a prevalence of arcuate uterus (65%).

[9-12] CUA may be associated with congenital renal anomalies

due to a close embryologic relation between the development

of the urinary and reproductive organs [13]: Evaluation of the

genital tract is recommended for women with major urologic

anomalies. Congenital uterine anomalies are not uncommon:

reported population prevalence rates in individual studies varying between 0.06% and 38%, and the observed wide variation

is possibly due to the assessment of different study populations

and the use of different diagnostic techniques [14]. Chan et al.

conducted a systematic review of studies evaluating the prevalence of congenital uterine anomalies in the unselected population and in women with a history of infertility, including those

undergoing IVF treatment, miscarriage, infertility and recurrent miscarriage combined, and preterm delivery. This review

evaluated that the prevalence of uterine anomalies diagnosed

by optimal tests was 5.5% in an unselected population, 8% in

infertile women, 13.3% in those with miscarriage and highest

at 24.5% in infertile women who also had a history of miscarriage [9]. There are many classifications of CUAs (Table 2): The

first of these reported by Cruveilher, Foerster and von Rokitansky in the mid-19th century, then the classification introduced

by Buttram and Gibbons in 1979 that was later revised by the

American Fertility Society (AFS), now known as the American

Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) [15]. The anomalies

were classified as: hypoplasia/agenesis, unicornuate, didelphys,

bicornuate, septate, arcuate and Diethylstilboestrol (DES) drugrelated. However this classification included only uterine anomalies with the exclusion of cervical and vaginal anomalies, did

not classify combined or complex anomalies and the arcuate

uterus being included as a separate class. The European Society

of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) and the European Society for Gynecological Endoscopy (ESGE) developed a

new updated classification system through a structured Delphi

procedure [7]. Uterine anomalies are classified into seven main types: U0, normal uterus; U1, dysmorphic uterus (infantile or Tshaped); U2, septate uterus; U3, bicorporeal uterus (partial and

complete—bicornuate and didelphys); U4, hemi uterus (unicornuate based on AFS); U5, aplastic uterus; U6, for unclassified

cases. Combined laparoscopy and hysteroscopy in considered

the gold standard test among the main diagnostic tools, which

also includes ultrasonography, hysterosalpingogram, sonohysterogram and MRI. Hysterosalpingogram, a common instrument for fertility investigation, can evaluate the uterine cavity

but can’t study the external uterine contour and can’t differentiate between bicornuate and septate uteri. 2D transvaginal

ultrasound is minimally invasive and a less expensive way to

study uterine morphology, however 3D transvaginal ultrasound

is considered the less invasive gold standard tool for the study

of uterine anomalies: three orthogonal planes can be viewed in

different modes to study the external and internal uterus contours. The diagnostic accuracy of 3D ultrasound is reported as

97.6% with sensitivity and specificity of 98.3% and 99.4% respectively [7].

Conclusion

Müllerian anomalies, though not uncommon, can present

significant diagnostic challenges due to their diverse manifestations. In this paper, we explored a particularly rare syndrome

that necessitated a complex and multi-disciplinary approach,

combining both surgical and hysteroscopic techniques. The intricacies of this case underscore the importance of a comprehensive diagnostic and therapeutic strategy to address such

unique and multifaceted conditions effectively. Our discussion

detailed the necessity for a collaborative effort among various medical specialties, including gynecology, radiology, and

surgery. This multidisciplinary team approach is essential not

only for accurate diagnosis but also for the development of a

tailored treatment plan that meets the specific needs and expectations of the patient. By involving specialists from different fields, we can ensure a more thorough understanding of the

condition and provide a higher standard of care. Moreover, this

case emphasizes the importance of considering the patient’s

individual circumstances and goals in the treatment plan. The

involvement of a diverse medical team allows for a more holistic

view, integrating different perspectives and expertise to achieve

the best possible outcomes. Therefore, we advocate for the

establishment of specialized centers with dedicated teams to

manage complex Müllerian anomalies, as this approach is crucial for optimizing patient care and advancing our understanding of these rare conditions.

Declarations

Author contributions: All authors approved the final version

of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Study registration: Not applicable

Disclosure of interests: The authors declare no conflicts of

interests.

Ethical approval: Ethics committee approval was not necessary since the study was a summary of data and outcomes of

routine management (without direct intervention) and not an

experimental protocol. We ensured the complete anonimacy of

the patients.

Informed consent statement: Written informed consent was

obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data availability statement: All data are reported in the text.

The data that support the findings of this study are available on

the main medical databases.

References

- Pfeifer SM, Attaran M, Goldstein J, Lindheim SR, Petrozza JC, et al. ASRM müllerian anomalies classification 2021. Fertil Steril. 2021; 116(5): 1238-52.

- Bortoletto P, Romanski PA, Pfeifer SM. Müllerian Anomalies: Presentation, Diagnosis, and Counseling. Obstet Gynecol. 2024; 143(3): 369-77.

- Ludwin A, Pfeifer SM. Reproductive surgery for müllerian anomalies: A review of progress in the last decade. Fertil Steril. 2019; 112(3): 408-16.

- Green LK, Harris RE. Uterine anomalies. Frequency of diagnosis and associated obstetric complications. Obstet Gynecol. 1976; 47(4): 427-9.

- Rock JA, Schlaff WD. The obstetric consequences of uterovaginal anomalies. Fertil Steril. 1985; 43(5): 681-92.

- Raga F, Bauset C, Remohi J, Bonilla-Musoles F, Simón C, et al. Reproductive impact of congenital Müllerian anomalies. Hum Reprod. 1997; 12(10): 2277-81.

- Grimbizis GF, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Saravelos SH, Gordts S, Exacoustos C, et al. The Thessaloniki ESHRE/ESGE consensus on diagnosis of female genital anomalies. Gynecol Surg. 2016; 13: 1-16.

- Tomazevic T, Ban-Frangez H, Ribic-Pucelj M, Premru-Srsen T, Verdenik I. Small uterine septum is an important risk variable for preterm birth. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007; 135(2): 154-7.

- Saravelos SH, Cocksedge KA, Li TC. Prevalence and diagnosis of congenital uterine anomalies in women with reproductive failure: a critical appraisal. Hum Reprod Update. 2008; 14(5): 415-29.

- Prasannan L, Rekawek P, Kinzler WL, Richmond DA, Chavez MR. Assessing müllerian anomalies in early pregnancy utilizing advanced 3-dimensional ultrasound technology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2024; S0002-9378(24)00529-5.

- Fedele L, Vercellini P, Marchini M, Ricciardiello O, Candiani GB. Communicating uteri: Description and classification of a new type. Int J Fertil. 1988; 33(3): 168-72.

- Grimbizis GF, Camus M, Tarlatzis BC, Bontis JN, Devroey P. Clinical implications of uterine malformations and hysteroscopic treatment results. Hum Reprod Update. 2001; 7(2): 161-74.

- Heinonen PK. Distribution of female genital tract anomalies in two classifications. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016; 206: 141-6.

- Chan YY, Jayaprakasan K, Zamora J, Thornton JG, Raine-Fenning N, et al. The prevalence of congenital uterine anomalies in unselected and high-risk populations: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2011; 17(6): 761-71.

- The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, müllerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1988; 49(6): 944-55.

- Connell M, Owen C, Segars J. Genetic Syndromes and Genes Involved in the Development of the Female Reproductive Tract: A Possible Role for Gene Therapy. J Genet Syndr Gene Ther. 2013; 4: 127.