Introduction

A history of recurrent gastric or duodenal ulcers could indicate a gastrinoma, also known as Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome

(ZES). A gastrinoma is a neuroendocrine tumor that causes

inappropriate gastrin secretion, ultimately causing gastric acid

hypersecretion. This leads to symptoms of acid reflux, gastric

and duodenal ulcers, and anemia. For a diagnosis of ZES to be

confirmed, there must be evidence of hypersecretion of gastrin

and a decreased gastric pH. A serum gastrin level >1000 pg/mL

and a gastric pH of 2 are considered to be diagnostic for gastrinoma. Specific studies such as NG tube fluid aspiration analysis

or upper GI endoscopy can be used to measure the pH of the

stomach. CT, MRI, or endoscopic ultrasound scans can then be

used to localize the primary tumor. It should be noted that CT

scans are not sensitive to small liver lesions, so MRI is a better

option if metastatic disease is suspected [1]. Another technique

that is used to localize gastrinomas is the octreotide scan or somatostatin receptor scintigraphy. This involves the administration of radio-labeled octreotide, which has selective binding to

somatostatin receptors found on gastrinoma tumor cells. It has

Annals of Surgical

Case Reports & Images

high sensitivity and specificity for primary tumor detection and

metastatic lesions. Combined with single-photo emission CT,

this has shown an even higher sensitivity and specificity than CT

or octreotide scan imaging alone.

Gastrinomas are located mostly in the gastrinoma triangle;

the superior border of the triangle is the confluence of the cystic and common bile ducts, the inferior border is the second and

third portions of the duodenum, and the medial border is the

neck of the pancreas [2]. In the majority of cases, pancreatic

lesions have worse prognoses than duodenal lesions and are

more often associated with metastatic disease. About 25-33%

of patients who have gastrinomas develop them secondary to a

syndrome called Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1 (MEN-1)

syndrome [3]. This condition involves tumors of the parathyroid

gland, pituitary gland, and pancreas. Management of sporadic

gastrinomas compared to those associated with MEN-1 syndrome varies slightly, so it is important to make the distinction

between the two during the initial diagnosis. In patients with

MEN-1, in addition to symptoms of gastrin hypersecretion,

there would be signs of hyperparathyroidism, such as hypercalcemia, and symptoms of a pituitary adenoma. MEN-1 syndrome with hyperparathyroidism leads to increased serum calcium, a known stimulator of gastrin release from gastrinomas.

Because of this, patients with MEN-1 syndrome have increased

resistance to anti-secretory medical treatments and require different doses of treatment drugs than patients who have sporadic ZES [4]. Another difference between MEN-1-related gastrinomas and sporadic gastrinomas is that the former is usually

associated with duodenal lesions, while the latter lesions usually localize in the pancreas. Sporadic pancreatic gastrinomas

metastasize to regional lymph nodes in approximately 60% of

patients, and to the liver in 10-20% of patients, a much higher

frequency than that of duodenal gastrinomas. The 10-year survival rate of those patients with sporadic disease is therefore

much lower than in patients with duodenal gastrinomas [3].

Symptomatic treatment starts with Proton Pump Inhibitors

(PPIs), however, in cases where the gastrinomas metastasize,

PPIs alone are not adequate for relief. Octreotide injections

can also stabilize gastrin secretion symptoms, thereby reducing

symptoms, but surgery is the only curative treatment to this day.

Surgery is useful in controlling the increased secretion of acid by

directly removing the secreting cells of gastrin and any metastases. If the metastases are unresectable, however, resecting the

primary tumor is still beneficial as long as 80-90% of the mass

can be safely removed [5]. After the procedure, it is important

to monitor gastrin and chromogranin A, a neuroendocrine biomarker, levels to check for recurrence or incomplete removal of

the disease. In this case report, we present a 59-year-old female

with a history of recurrent duodenal ulcers only to be found to

have a pancreatic gastrinoma with extensive liver metastasis.

Gastrinomas with liver metastasis are associated with significantly reduced survival, therefore our patient’s best chance of

improving her survival rate was to undergo aggressive resection

of the tumor and its associated liver metastases.

Case presentation

A 59-year-old female with a past medical history of hypertension, GERD, and a perforated duodenal ulcer presented to

the ED with epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, and melena in

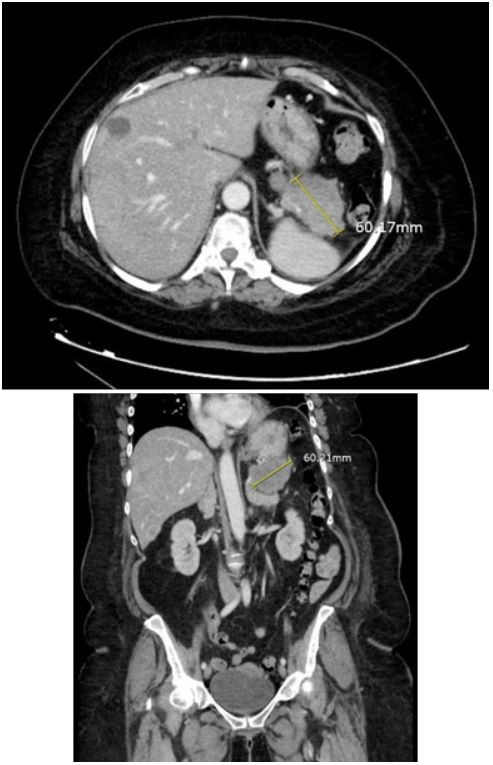

November of 2023. A CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis

showed a 6 cm pancreatic tail mass with numerous liver lesions

(Figure 1). The patient continued to pass dark stools throughout her hospital stay. An EGD done a few days later showed a

non-bleeding 2 cm duodenal ulcer. The ulcer was treated with

bipolar cautery. The second, third, and fourth portions of the

duodenum were normal. H. pylori testing came back negative.

Her EGD done in 2022 also showed evidence of gastritis, esophagitis, and two ulcers in the duodenum, indicating a chronic history of peptic ulcer disease. The patient, however, continued to

have symptomatic anemia and pass dark stools. A mesenteric

angiogram with gastroduodenal artery embolization was done,

and the patient noted relief of melena; she was discharged to

follow up as an outpatient. 5 days post-discharge, the patient

came back to the ED presenting with weakness, inability to ambulate, and melena as of that morning. She was initially hypotensive but this improved with fluids. Her CEA, CA 19-9 and AFP

were negative. Studies revealed gastrin levels to be 2745 pg/

mL, raising concern for her pancreatic mass to be a gastrinoma.

MRI showed a 5.0 mass in the tail of the pancreas, and multiple

masses within the liver measuring up to 6.0 cm, confirming the

diagnosis of a gastrinoma with liver metastases. She was then

started on octreotide three times a day. The patient was scheduled for a distal pancreatectomy and liver metastases. Platelets and hemoglobin remained stable, so the patient was taken for

surgery. During the procedure, the abdomen was inspected and

no diffuse carcinomatosis was found. The tumor at the distal

pancreas was visualized. The pancreas was dissected off the

retroperitoneum. The tumor was taken out and sent for a frozen section and came back with negative margins. 12 hepatic

tumor metastases were resected. The procedure was complicated by bleeding from a previously diagnosed duodenal ulcer.

The source of the bleeding was ligated after making a duodenotomy and suturing the bleeders using a three-point ligation

technique.

Discussion

With our patient’s history of peptic ulcer disease, her symptoms when she initially presented to the ED, and her increased

gastrin levels, the patient had a classic presentation of pancreatic gastrinoma. Imaging confirmed the diagnosis and the

presence of liver metastasis, and after a multidisciplinary board

discussion, the decision was made to proceed with surgical resection.

In cases that are associated with MEN-1 syndrome, diagnosis of the presence of a gastrinoma is not as straightforward as

many patients with MEN-1 only show symptoms of ZES after

the development of hyperparathyroidism. Hypercalcemia secondary to hyperparathyroidism can be the first sign of MEN-1,

and it is directly associated with the later development of hypergastrinemia [6]. As it stands today, surgery is the only curative management for gastrinoma with liver metastasis. PPIs and

H2 blockers are considered for symptomatic management during the early stages of the disease, when the gastrinoma and/or

metastases are not resectable, or in cases where there is widespread metastasis.

Hepatic and/or gastroduodenal artery embolization is another therapeutic option to reduce metastatic symptoms as well as

control peptic ulcer symptoms. Liver metastases get their blood supply from the hepatic artery, so embolization of the hepatic

artery can reduce symptoms of the metastases. One must factor in the possibility of postembolization syndrome, however,

which can present as fever, nausea, loss of appetite, and abdominal pain. However, in cases as severe as this one, such a

risk does not outweigh the benefits of the procedure [7].

As true with most metastatic diseases, the treatment options

are limited. Chemotherapy is an option for patients with distant

metastases, however, this treatment method has limited effects

on disease regression and can prove to be more toxic than helpful to the patient. Studies also show that octreotide administration can control the growth of liver metastases and stabilize

serum gastrin secretion, but this will not rid the patient of the

disease itself. Shanshank et al. 2023 state that targeted therapies such as antiangiogenic modalities, multi-kinase, or mTOR

inhibition are upcoming new approaches to tackling delayed

tumor progression in patients with metastatic disease. These

novel therapies are still in the trial phase, however, so the most

effective treatment for gastrinoma is still surgical resection.

Lastly, orthotopic liver transplantation is currently being explored as an option for patients who have limited liver metastatic resectibility. The survival rate is similar to that of hepatic

resection, however, this needs to be studied further before it

can be a definitive option for such patients [8].

The extent and location of metastases are the most important determining factors for mortality. For metastatic disease,

removal of the primary tumor and as many metastases as possible is the goal to prevent further spread of the disease and

improve survival. As our patient did have extensive liver metastasis, there is a possibility that the disease has not been completely eradicated. Good post-operative care and consistent

follow-up are key for this patient; any sign of lingering disease

or recurrence should be caught early and treated immediately.

Checking serum gastrin levels and chromogranin A regularly

post-surgery is vital to monitor the disease regression.

Conclusion

Recognizing that a patient has ZES can be a challenge within itself. It can take a long time to diagnose as the symptoms

initially appear as non-specific manifesting as abdominal pain,

chronic diarrhea, GERD, and anemia. In patients with chronic or

recurrent ulcers, the diagnosis of gastrinoma should be high on

the list of differentials. If applicable, symptomatic management

with PPIs and imaging would be the next steps to identify the

tumor and the extent of its metastases. Surgical resection remains to be the only curative treatment, however, with upcoming advances in medicine, it may become possible to rely more

on medical treatments to aid in the curative process of ZES with

liver metastases.

References

- Rossi RE, Elvevi A, Citterio D, Coppa J, Invernizzi P, et al. Gastrinoma and Zollinger Ellison syndrome: A roadmap for the management between new and old therapies. *World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2021; 27(35): 5890-5907. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i35.5890

- Cingam SR, Botejue M, Hoilat, GJ, et al. Gastrinoma. In: StatPearls. 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441842/

- Anlauf M, Garbrecht N, Henopp T, Schmitt A, Schlenger R, et al. Sporadic versus hereditary gastrinomas of the duodenum and pancreas: distinct clinico-pathological and epidemiological features. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006; 12(34): 5440-5446. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i34.5440

- Norton JA, Foster DS, Ito T, Jensen RT. Gastrinomas: Medical or Surgical Treatment. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 2019; 47(3): 577-601. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2018.04.009

- Zheng M, Li Y, Li T, Zhang L, Zhou L. Resection of the primary tumor improves survival in patients with gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms with liver metastases: A SEER-based analysis. Cancer Medicine. 2019; 8(11): 5128-5136. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.2431

- Massironi S, Rossi RE, Laffusa A, Eller-Vainicher C, Cavalcoli F, et al. Sporadic and MEN1-related gastrinoma and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: differences in clinical characteristics and survival outcomes. Journal of Endocrinological Investigatio. 2013; 46(5): 957-965. doi: 10.1007/s40618-022-01961-w

- Jilesen AP, Klümpen HJ, Busch OR, van Gulik TM, van Lienden KP, et al. Selective Arterial Embolization of Liver Metastases from Gastrinomas: A Single-Centre Experience. ISRN Hepatology. 2013; 174608. doi: 10.1155/2013/174608

- Shao QQ, Zhao BB, Dong LB, Cao HT, Wang WB. Surgical management of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: Classical considerations and current controversies. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2019; 25(32): 4673-4681. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i32.4673.