Case report

A 13-year-old male presented to the emergency department

following an episode of gagging while eating grilled chicken. He

reported significant odynophagia and globus sensation. He had

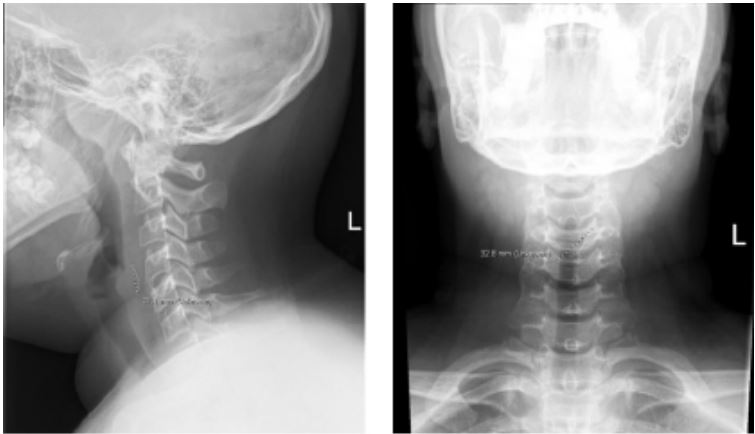

no symptoms of airway compromise. Neck radiograph was obtained which demonstrated a curvilinear radiopaque structure

measuring 3.2 cm in the region of the piriform sinus, presumed

to be a chicken bone given the history (Figures 1-2). ENT was

consulted and flexible laryngoscopy was performed. No foreign

body was identified.

The patient was taken to the OR for airway exam, esophagoscopy, and foreign body removal. Intraoperatively, there was

a small area of edema in the postcricoid region with a small

mucosal entry point. This was palpated with a right angle and a

small amount of purulence was expressed. The right angle was

used to probe the wound, confirming the presence of a tract. To

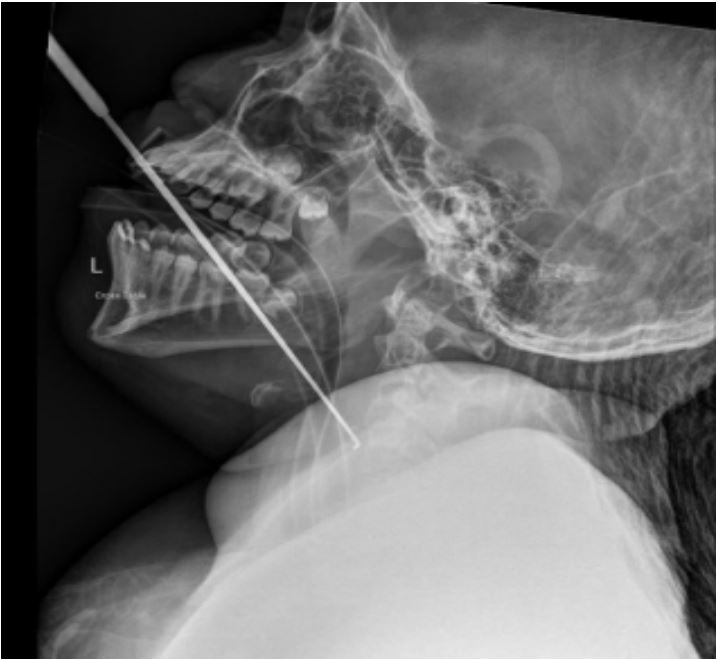

localize the foreign body, an ETT was placed into the esophagus

and the right angle was positioned within the entry point while

an intraoperative x-ray was obtained (Figure 3). This confirmed

the location of the foreign body within the posterior esophageal mucosa. The microscope was brought into the room to allow for two-handed instrumentation. A sickle knife was used

to make a vertical incision in the posterior esophageal mucosa.

A combination of scissors, sickle knife, right angle, and suction

were used to dissect and probe the wound. Precise localization

of the object was difficult due to its small size. To aid in localization, a magnet was fashioned to the end of a nasogastric tube

and used to co-localize the magnetic foreign body within the

posterior esophageal mucosa. Once the foreign body was visible within the wound, alligator forceps were used to grab and

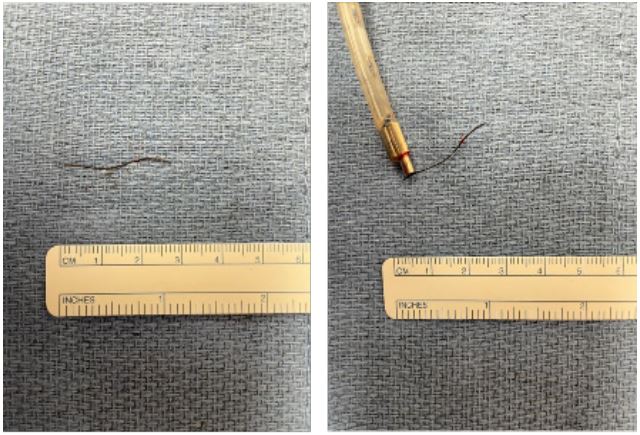

remove the foreign body. The foreign body was consistent with

a grill brush bristle measuring 2.8 cm (Figure 4-5).

A dobhoff tube was placed in the operating room, and the

patient was admitted overnight for observation. He underwent

a barium esophagram on post-operative day 1 with no evidence

of esophageal leak, and he was subsequently discharged home.

Discussion

Foreign bodies which are sharp may become embedded

within the upper aerodigestive tract when ingested. While this

is a relatively benign complication of foreign body ingestion,

it can lead to serious complications including retropharyngeal

abscess, esophageal perforation, or migration into the mediastinum with associated mediastinitis. One review notes bristle

migration occurring in 21% of upper aerodigestive tract cases

after initial presentation (Miller et al. 2021) [1]. For this reason, prompt identification and removal of a retroesophageal

foreign body is crucial. Even with the use of preoperative and

intraoperative imaging, precise localization of the object may

be challenging. Grill brush bristle ingestion is a public health issue and carries a high risk of becoming embedded within the

soft tissue of the aerodigestive tract. The national weighted

estimate of patients evaluated in the emergency department

after wire bristle ingestion in America between 2002-2014 was

1,700 (Baugh, Hadley, and Change, 2016) [2]. Though the object

in this case was originally presumed to be a chicken bone based

on history, the appearance on intraoperative imaging led us to

suspect a grill brush bristle which prompted us to use a magnet

to aid in its localization.

The use of a magnet to remove metal foreign bodies from

the gastrointestinal tract is not an entirely novel concept. One

article describes the possibility of using a magnetic tube to remove metal foreign bodies, which can potentially be utilized

in the awake patient if the object is in the proximal esophagus

and not embedded (Choe and Choe, 2019) [3]. Another case we

found describes a technique in which a snared magnet is used

to endoscopically remove a nonembedded paperclip within the

stomach (Coash and Yu, 2012) [4]. However, to our knowledge,

intraoperative use of a magnet to aid in the localization of an

embedded metal foreign body within the esophageal wall has

not been previously described in the literature.

Naunheim describes a similar presentation of a grill brush

bristle embedded in the hypopharynx. They used suspension,

microscope, and localized intraoperative fluoroscopy (2015) [5].

While intraoperative imaging is helpful for appropriate localization, we found that more accurate localization of the grill brush

bristle was accomplished with the addition of a magnet to this

technique. In hindsight, if we had employed the magnet earlier

in the case, we may have been able to identify the object prior

to obtaining intraoperative imaging and could have potentially

avoided unnecessary radiation.

Conclusion

Grill brush bristles may unknowingly be ingested and become embedded within the aerodigestive tract. Magnets are a

useful adjunct tool that can aid in both the intraoperative localization and removal of grill brush bristles and other metal

foreign bodies.

References

- Miller N, Noller M, Leon M, Moreh Y, Watson NL, et al. Hazards

and management of wire bristle ingestions: A systematic review.

Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2021; 167(4): 632-644.

- Baugh TP, Hadley JB, Chang CW. Epidemiology of wire‐bristle

grill brush injury in the United States, 2002‐2014. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2016; 154(4): 645-649.

- Choe JY, Choe BH. Foreign body removal in children using Foley

catheter or magnet tube from gastrointestinal tract. Pediatric

Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition. 2019; 22(2):

132.

- Coash M, Wu GY. Endoscopic removal of a long sharp metallic

foreign body by a snared magnet: An attractive solution. Journal

of Digestive Diseases. 2012; 13(4): 239-241.

- Naunheim MR, Dedmon MM, Mori MC, Sedaghat AR, Dowdall

JR. Removal of a wire brush bristle from the hypopharynx using

suspension, Microscope, and fluoroscopy. Case Reports in Otolaryngology. 2015; 1-4.