Introduction

Atraumatic Splenic Rupture (ASR) is a rare pathological entity relative to traumatic cases, being referred to as a spontaneous rupture in the presence of a histologically proven normal

spleen, conversely nomenclature stipulates it is referred to as

a pathological rupture in diseased spleens [1]. ASR carries with

it a risk of mortality which has been reported to be as high as

12.2% [2], given the life-threatening potential a prompt diagnosis and subsequent management is critical. However, the aetiology of ASR is wide ranging and often and the clinical diagnosis

can be obscured by signs and symptoms being attributed to the

underlying disease process, thus requiring a high index of clinical suspicion.

Case presentation

A 41 year old female with no past medical history of note

presented to the emergency department with a 3 day history

of coryzal symptoms, a productive cough of yellow sputum, exertional shortness of breath, left sided pleuritic chest pain, myalgia and confusion. She was a previous cigarette smoker with

a 9 pack year history and was currently vaping. Initial observations on admittance to hospital revealed an Early Warning Score

(EWS) of 1 for a blood pressure of 106/64 mmHg, clinical examination was unremarkable beyond scanty left basal crepitations

on auscultation, biochemical anomalies were a c-reactive protein of 83, platelet count 80x109

/L, prothrombin time 11.5 seconds and a lymphocyte count 0.36x109

/L with a normal overall white cell count. A chest x-ray revealed left lower zone patchy

infiltrates and a respiratory viral screen returned positive for

influenza B virus. She was commenced on intravenous antibiotics and oral oseltamivir for viral pneumonia with suspected

secondary bacterial infection, being transferred to a respiratory

ward. On day 2 of her admission she complained of worsening

left sided chest/hypochondriac pain and continued to be hypotensive, presumed to be secondary to the underlying infection,

before rapidly deteriorating later in the evening with an EWS

of 10. A venous blood gas revealed a metabolic acidosis with

a lactate of 5.6 mmol/L and a Haemoglobin (Hb) 7.8 g/dl. She

was treated initially for septic shock before a repeat blood gas

shortly after boluses of intravenous fluid showed a falling Hb

to 4.4 g/dl, confirmed on laboratory results. The major haemorrhage protocol was declared with administration of blood

products to also correct clotting before transfer to radiology for

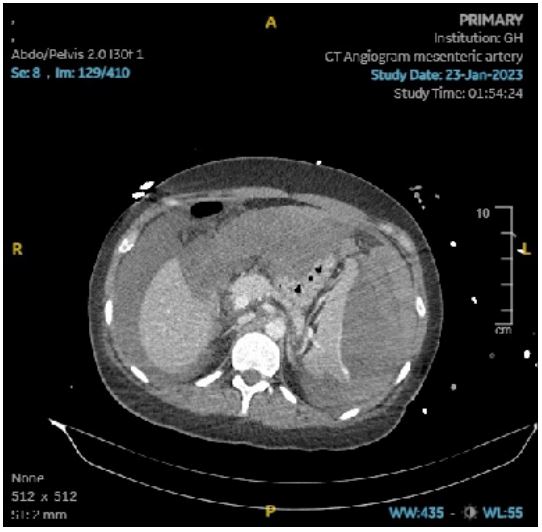

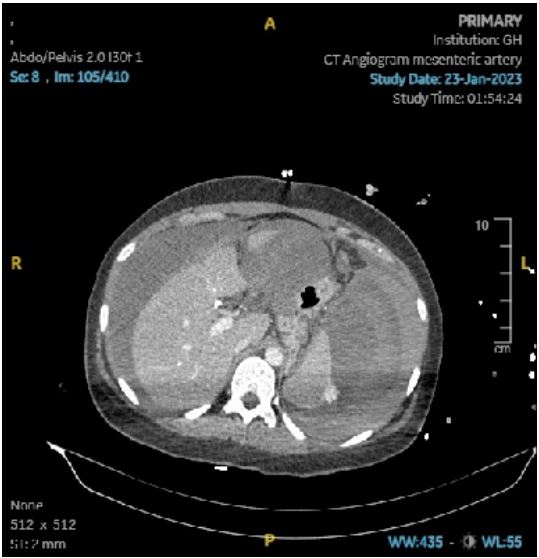

an urgent CT chest, abdomen and pelvis with a mesenteric angiogram. Imaging findings revealed a subcapsular splenic haematoma, with extensive intraperitoneal extension and active

contrast extravasation consistent with ongoing haemorrhage

confirming ASR with an American Association for the Surgery of

Trauma (AAST) grade 4 splenic injury. This was alongside scattered patchy consolidative changes throughout the lungs, with

atypical appearances, sparing the dependant areas being predominantly limited to the peri-hilar and anterior segments of

the upper lobes as well as the right middle lobe and left lingula.

The patient underwent an emergency open splenectomy later

that evening. She made an uneventful recovery and was discharged home at day 7. Macroscopically the specimen was of

normal appearances apart from the obvious haemarrhage. Microscopically the specimen retained architecture of the white

pulp with normal immunohistochemistry, there was some expansion of the red pulp indicating a degree of mild congestion

but no specific cause of the splenic rupture was identified.

Table 1: Examples of aetiology.

| Aetiology |

Examples |

| Neoplatic |

Hodgkin’s symphoma and

primary/secondary

neoplas-

tic disorders

such as angiosarcoma and

lung cancer

|

| Infectious |

Viral, bacterial, fungal or

protozoal in nature such

as

malaria

|

| Inflammatory |

Pancreatitis, systemic lupus

erythematosus

|

| Treatment related |

Haemodialysis, oral

anticoagulants

|

| Mechanical disorders |

Pregnancy, congestive

splenomegaly secondary to

liver

cirrhosis and portal

hypertension

|

Discussion

The management of ASR can be broadly divided into surgical

with either a total splenectomy or organ preserving surgery and

non-surgical with arterial embolization or conservative “watchful waiting”. Whilst there remains no generalised consensus,

the decision is influenced by a number of factors including, but

not limited to, the degree of haemodynamic instability and ultimately the clinical condition of the patient, grade of splenic

injury, availability of specialist interventional radiology services

for arterial embolization and the suspected cause, with malignant causes favouring total splenectomy [3]. In a large systematic review of ASR Renzulli et al found that of 774 patients,

85.3% underwent surgery within 24 hours and of the remainder

managed non-surgically, 17% eventually underwent secondary splenectomy due to rebleeding and haemodynamic compromise [2]. However the benefits of non-surgical management

must not be disregarded due to the spleens fundamental role

in immunity and conferring protection against encapsulated

organisms [4]. The underlying aetiological association of ASR

is expansive and can be broadly categorised into distinct subgroups [2,5].

Of the above sub-groups Renzulli et al. found that malignant

haematological, viral infectious and inflammatory disorders accounted for 42.1% of the 845 patients [2]. In a systematic review of ASR in 613 patients, Aubrey-Bassler et al found that the

most common associated pathological processes were infectious in nature [6]. ASR may present with an array of clinical

symptoms and signs obfuscating an accurate and time critical

diagnosis. This is further compounded by the wide variety of

aetiological conditions which may contribute to it. Given the associated high mortality, and can be attributed to any number

of the associated aetiological conditions. Patients may present

with abdominal pain, not solely in left upper quadrant as commonly depicted in textbooks as a result of hemoperitoneum

thus imitating commoner causes of an acute abdomen. They

may also present in the absence of any pain and instead with

vague symptoms of shoulder tip pain referred to as Kehr’s sign,

chest pain, nausea and vomiting as well as weakness [7].

Conclusion

To summarise we have outlined the first documented case of

a spontaneous splenic rupture associated with Influenza B virus

in English literature. Although the majority of patients with ASR

will undergo an emergency splenectomy, non-surgical management such as splenic artery embolization should be considered

in clinically appropriate cases to preserve splenic function and

thus avoid the need for vaccinations and lifelong antibiotic therapy. The associated pathological entities of ASR are vast and can

present in a manner which strays from a textbook presentation,

given the associated mortality a high index of clinical suspicion

is required and this case presentation serves as a gentle reminder for clinicians to not overlook ASR in their list of differential

diagnoses.

References

- Ciftci A, Colak E. Characteristics and surgical outcomes of patients with atraumatic splenic rupture. Journal of international

medical research. 2022; 50(2): 03000605221080875.

- Candinas D, Gloor B, Hostettler A, Renzulli P, Schoepfer M. Systematic review of atraumatic splenic rupture. British Journal of

Surgery. 2009; 96(10): 1114-1121.

- Clercq S, Guy s. Splenic rupture in community acquired pneumonia: A case report. International journal of surgical case reports.

2016; 29: 85-87.

- Chi W, Fang ZT, Lin C, Lin JL, Luo JW, et al. Splenic Artery Embolization and Splenectomy for Spontaneous Rupture of Splenic

Hemangioma and Its Imaging Features. Front Cardiovasc Med.

2022; 9: 925711.

- Christopher H, Jessica B, Robert P, Zayd A. Atraumatic Splenic

Rupture on Direct Oral Anticoagulation. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2022; 12(5): 84-87.

- Aubrey-Bassler FK, Sowers N. 613 cases of splenic rupture without risk factors or previously diagnosed disease: A systematic

review. BMC Emerg Med. 2012; 12: 11.

- Levitt MA, Lieberman ME. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen: a

case report and literature review. Am J Emerg Med. 1989; 7(1):

28-31.