Introduction

Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma (ATC) is known as a highly aggressive type of cancer with a very poor prognosis [1,4]. ATC is a

form of undifferentiated thyroid carcinoma and represents 1-2%

of all thyroid tumours [2,5,6]. Despite being extremally rare, it

accounts for up to 50% of all thyroid cancer-related mortalities

[2,3]. The median survival rate varies, usually 3 to 6 months

after the diagnosis [1,2,4,7,8]. The overall 1-year and 5-year

survival is 10-20% and less than 10% respectively [4,6,7]. ATC’s

origin is unknown. As a form of undifferentiated thyroid cancer

it can arise de novo or from a pre-existing well-differentiated

thyroid tumour due to the accumulation of genetic alterations

[6,9,14]. ATC is exceptional because of its high aggressiveness,

fast growth, and strong invasiveness [5,6]. This type of cancer often presents with metastases to local and distant lymph

nodes, lungs, and liver [15,16]. ATC is more common in women

and people over the age 60 [2,8,15,17,18]. Distant metastases, age, and socioeconomic status are other known risk factors associated with poorer survival in these patients [15,19]. Various

strategies of treatment are used for ATC such as surgical resection, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or a

combination of different treatment methods [8,20]. Usually, the

treatment of choice depends on the specific situation [20,21].

Little is known about extrathyroidal ATC. We represent a current knowledge about ATC in extrathyroidal area focusing on

the primary retroperitoneal tumours. We also describe a very

unique case of a patient with a huge primary retroperitoneal

tumour of ATC origin with normal function and structure of thyroid gland.

Case report

A 72-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital due to a

high fever of up to 42 degrees Celsius, acute abdominal pain,

and loss of consciousness. Increasing abdominal growth and

abdominal pain lasted for more than a week. Abdomen ultrasound showed a massive cystic-solid abdominal mass causing

mass effect on surrounding organs.

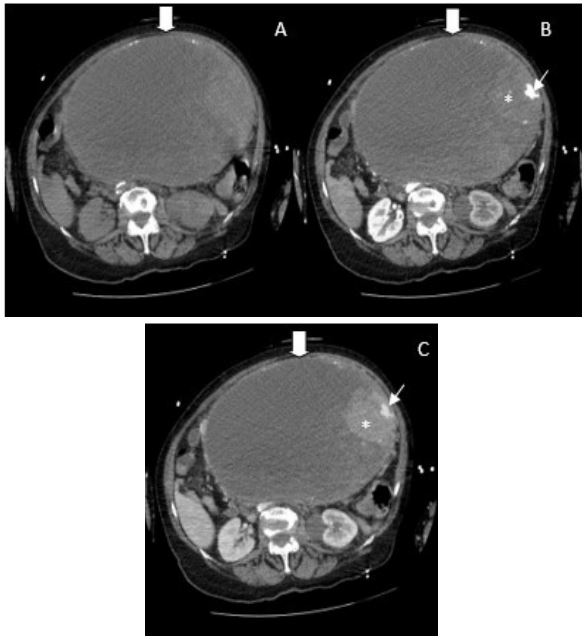

Computed Tomography (CT) imaging was made for diagnostic clarification, huge. ~26x23x27.5 cm in homogeneous (cysticsolid mass with calcinates) abdominal mass. (likely to be an

ovarian tumour) was detected causing left hydronephrosis (Figure 1) (Large intraabdominal well defined mass (large arrow)

with periferal calcifications, predominant cystic component and

solid contrast enchancing tissue (thin arrow) by the left wall,

where a small arterial pseudoaneurysm (asterix) is seen), 2).

Illness anamnesis, health, and family history were unknown

at that time due to severe patient status. Later the patient explained that she noticed an increasing size of her abdomen over

many years (around 30 years) but she did not consult with the

doctors. During check-up in the emergency department patient

was conscious but assessed as having SCORE 12 on Glasgow

Coma Scale (GCS), hemodynamically unstable, hypotonic and

having respiratory failure (hypoxia, acidosis). Increased inflammatory indicators (C-reactive protein 167 mg/l), procalcitonin

(174 µg/l), D-dimmers (31670 µg/L), lactate (>5 mmol/l), anaemia (haemoglobin 109 g/l) and coagulation indicators imbalance were detected. Due to large abdominal mass compression

of the left ureter which caused left hydronephrosis urologist

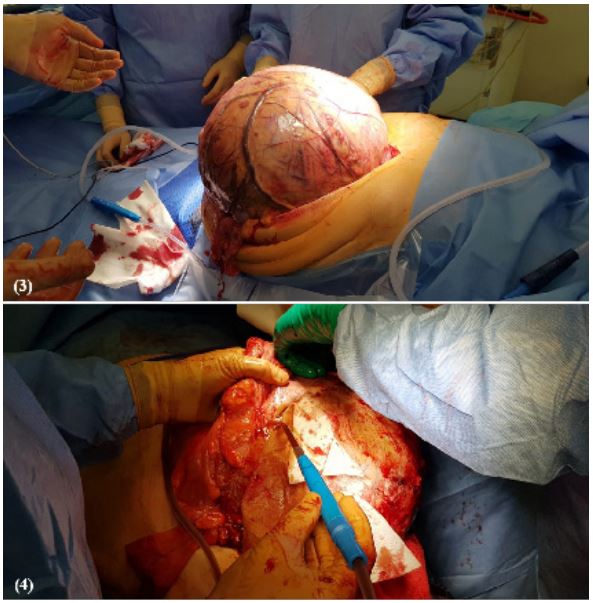

performed a left percutaneous nephrostomy. The patient underwent an urgent operation: extirpation of retroperitoneum

tumour with left hemicolectomy and formation of an end colostomy. The abdominal cavity was occupied with pathological

retroperitoneal mass in the mesentery of large intestines with a

very close connection with descending and sigmoid colons and

also invaded arteria mesenterica inferior (Figure 4). The postoperative course was smooth. After the operation conservative

treatment was provided: antibiotic therapy, vasopressors, analgesics, infusion therapy, anticoalition prevention, and other. In

dynamics, the patient’s condition improved, inflammatory and

uremia indicators decreased, and left kidney nephrostomy was

removed. The patient was discharged, and the whole duration

of hospitalization was less than two weeks. During the late postoperative period the patient had no health complaints. At that

time, results of histopathological analysis of the retroperitoneal

tumour came out: thyroid papillary carcinoma with anaplastic

carcinoma differentiation, invasion of anaplastic carcinoma to

the large intestine. After a month the patient was consulted

repeatedly. Blood tests (thyrotropin-releasing hormone, antithyroglobulin, thyroglobulin, a carcinoembryonic antigen) were

done, and results were in a normal range. A thyroid ultrasound was done, and only minor insignificant diffuse changes were

seen in thyroid tissue and one supraclavicular pathological

lymph node (7x15 mm) was detected on the left. Neck, chest,

abdomen, and pelvic CT was performed two months after the

operation, borderline left subclavicular lymph node (14x10 mm)

was seen, and no focal metastases in the lungs and internal organs were detected. The future treatment plan was discussed

by the multidisciplinary group of doctors (abdominal surgeon,

oncologist-chemotherapist, radiologist, endocrinologist). The

patient was suggested to undergo a positron emission tomography (PET) scan, and later have a biopsy taken from the borderline left subclavicular lymph node, no adjuvant treatment was

suggested at that time. However, the patient refused further

investigation and treatment. Overall, the patient survived more

than 5 months after the operation, no adjuvant treatment was

given. The patient did not have any complains, and no signs of

disease recurrence or metastases were seen except for the borderline left subclavicular lymph node. In addition, the patient is

still alive 2 years after the primary operation and initial diagnosis of primary retroperitoneal cancer with ATC differentiation.

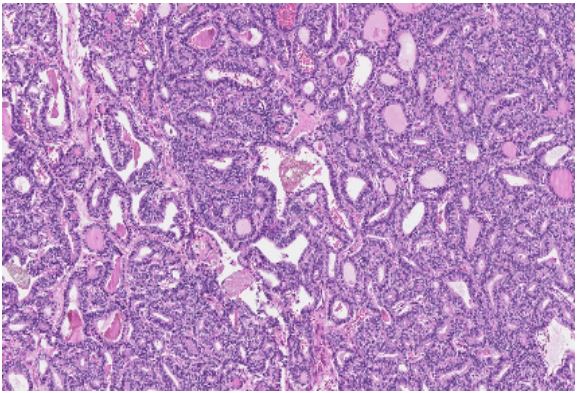

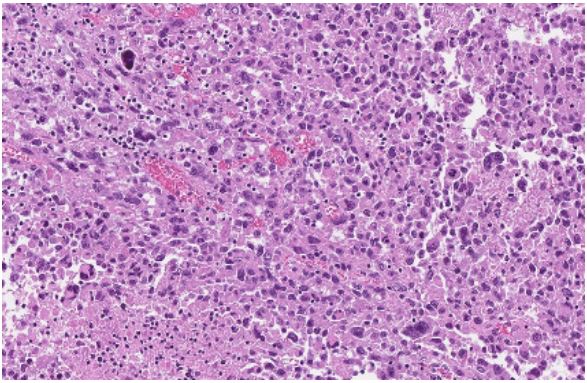

A detailed description of histopathological analysis was done.

The resected retroperitoneal tumour is a thyroid papillary carcinoma with anaplastic carcinoma differentiation and invasion

to the large intestine. The resected yellow-grey retroperitoneal

mass measuring 30 cm in the greatest dimension with necrotic areas and haemorrhages in the centre. Extensive sampling

showed various sizes of follicular, glandular and papillary structures, atypical in shape epithelium cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and oval, round slightly polymorphic nuclei. Little mitosis

was found. The malignant tumour was encapsulated. Less than

5% of the tumour was composed of large atypical epithelioid

cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, polymorphic, vesicular nuclei,

and conspicuous nucleoli and high mitotic activity (anaplastic

transformation). More clusters of atypical cells were found in

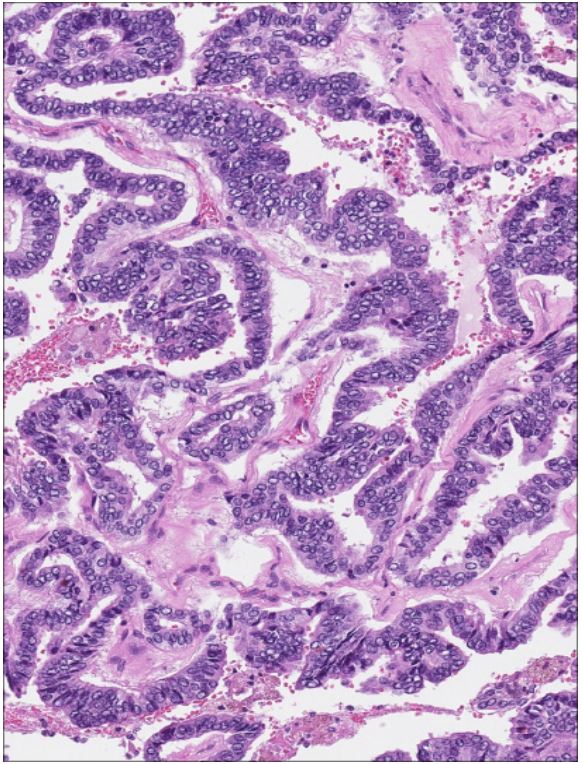

fibrotic capsules with overgrowth (Figure 5-7 (High-grade tumour component, making up 5% of total tumour area, is composed of large epithelioid cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm,

polymorphic nuclei with extensive necrosis, apoptotic and mitotic figures. Some tumour cells are large with multiple nuclei

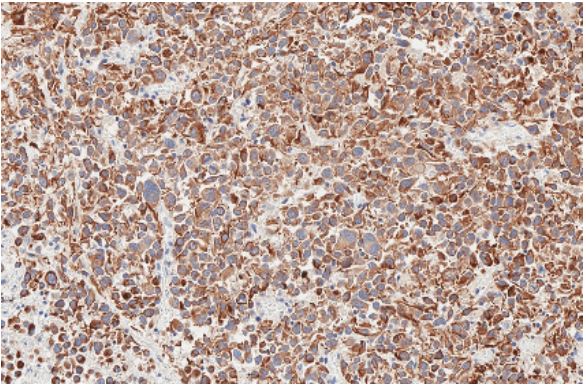

(Photomicrograph, HE stain))). Immunohistochemical staining

was also performed. The tumour cells were strongly positive

for Anti-Cytokeratin (Cam5.2), Pan-Cytokeratin (PanCK), Cytokeratin 19 (CK19), thyroglobulin, and Thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1). Half of the cells showed positive results for PAX8

and Epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), and less than 5% of

cells – protein Ki67. P53, BRAF, WT1, synaptophysin, estrogen

receptors were negative (Figure 8). Histological analysis and the

overall immunohistochemical profile were concluded to final

diagnosis of a primary retroperitoneal tumour of thyroid papillary carcinoma with focal transformation to thyroid anaplastic

carcinoma of high grade (G4) malignancy (anaplastic carcinoma

giant cell carcinoma type).

Anaplastic carcinoma can be found in the retroperitoneal

area due to several reasons: as primary thyroid cancer, as a

struma ovarii with malignant transformation and metastases to

the retroperitoneal area, or as a metastases of papillary cancer

with anaplastic transformation when a primary tumor is found

in the thyroid. According to the blood tests and imaging results,

the patient in our case presented with primary retroperitoneal

cancer with differentiation of ATC. Written informed consent

from the patient for the publication of any possible identifiable

information (images and case details) was obtained.

Discussion

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma is known as a very rare and

lethal thyroid cancer [1,3,6]. Little is known about ATC in the

extrathyroidal area. The origin of retroperitoneal cancer with

anaplastic transformation can be explained as a primary thyroid

cancer with anaplastic transformation, as a struma ovarii with

malignant transformation and metastases to the retroperitoneal area, as a metastases of papillary cancer with anaplastic

transformation when a primary tumour is found in the thyroid

or as a retroperitoneal monodermal teratoma composed of

papillary cancer with anaplastic transformation [31]. We presented a very unique example of primary retroperitoneal cancer with ATC differentiation but there are known several other

similar cases. One published case represents a 75-year-old male

who had ATC developed between the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the common carotid artery. The thyroid had no changes

and it was totally separated from the tumour. The biopsy of the

thyroid or total thyroidectomy was not performed and histological analysis was not done. Possibly the ATC transformed

from papillary thyroid carcinoma to an extrathyroidal tumour.

Despite known poor survival, the patient lived 3.5 years without incidence of tumour recurrence after total resection and

around 5 years after the first symptoms [17]. Another studied

case of ATC manifestation in the extrathyroidal area was about

a 63-year-old female. She complained about a rapidly growing

abdominal mass during a month period and increased in size

neck mass over a week which caused dysphagia, shortness of

breath, and hoarseness. Important to note is that she had a history of goiter. The patient was diagnosed with ATC metastases

in the abdominal subcutaneous fat layer, and lungs. Palliative

radiotherapy was initiated for the neck area, and later systemic

chemotherapy was administrated. However, due to the aggressive nature of ATC, the patient experienced vocal cord paralysis

with severe airway problems and died around 9 weeks after the

hospitalization because of respiratory distress [32]. A similar situation was seen in a 64 year-old male who was examined due to

growing abdominal mass that was causing a mass effect on the

stomach, left adrenal gland, kidney, and pancreas. The patient

experienced total thyroidectomy 30 years ago because of papillary thyroid carcinoma and had an adjuvant radioactive iodine

treatment. Later metastases in the cervical lymph nodes and

left axilla were detected. The biopsy was taken from the growing retroperitoneal mass. According to the immunohistochemical profile, the results were similar to anaplastic transformation

in metastatic papillary thyroid cancer. The patient had a palliative resection surgery and died 3 weeks after the operation because of large bowel obstruction and sepsis [33].

ATC is associated with high aggressiveness because of fast

growth, high tendency for invasiveness, and low responsiveness

to most therapies [5,6]. ATC cases are staged as IV-stage thyroid

cancer due to ATC’s very aggressive nature as is followed by the

American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) guidelines. Based

on the invasion, the extent of the tumour, and distant metastases, ATC is divided into stages: IVA stage (T1T3a, N0, M0) is

a tumour localized to the thyroid gland without lymph node

involvement (N0) and distant metastasis (M0). Stage IVB represents a primary tumour with gross extrathyroidal extension

(T3b,T4), and possible involvement of locoregional lymph nodes

(≥N1). IVC stage (any T, any N, M1) is a tumour with distant metastases (M1) [8].

Fine needle aspiration biopsy of a rapidly growing thyroid

or any other extrathyroidal mass or an abnormal lymph node

is the best method to diagnose ATC. However, it is difficult to

detect ATC in the early stage. Mostly ATC is diagnosed in an advanced stage, being a big mass, compressing surrounding structures like the trachea and causing symptoms such as dyspnoea,

dysphagia, neck pain, hoarseness, or other [2,8,22]. Nevertheless, ATC can also be detected incidentally during routine physical examination or urgent operations [2].

ATC is usually detected in older patients over 60 years

[2,8,18,23]. Also, it is more common in women than in men

[8,17,18,23]. Other known possible risk factors of this cancer

are obesity, a history of known thyroid nodular disease, and

malignancy in other sites such as prostate adenocarcinoma,

uterine cancer, and colic gastrointestinal stromal tumours [15].

There are more known factors that influence the survival of patients like distant metastases, socioeconomic status, and treatment strategy [2,8,15,19]. Local invasion is usually seen in ATC

cases. Also it is very common to detect metastasis in local or

distant lymph nodes, lungs, liver, and bones [15,16,22,24,25].

The aetiology of ATC is still unknown [2,9]. There are several hypotheses: it arises de novo or from the same mass of differentiated or poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma [3,6,10].

Histological analysis of ATC is difficult since it is composed of

undifferentiated thyroid follicular cells and is likely to appear

in a multitude of microscopic variations [6,13,16]. Various immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis are made to determine their epithelial origin [15]. As for all malignant tumours

ATC has some certain features of high malignancy: invasiveness,

extensive tumour necrosis, marked nuclear pleomorphism, and

high mitotic activity [16,26]. The cell phenotype is known to be

of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition type [1]. Morphology of the cells might be different: pleomorphic giant, spindled

and squamous [16,27]. Also in some ATC cases paucicellular,

rhabdoid or small cell variants can be found [16,26]. All of this

makes ATC diagnosis more difficult and delayed [27]. Moreover,

an association has been found between ATC and accumulated

genetic alterations that are responsible for the regulation of the

MAPK and PI3K/AKT signalling pathways. These pathways affect

BARF, KRAS, PTEN and other genes that are known for several

modulatory cell functions: growth, survival and proliferation

[9,10].

The survival rate of ATC is very poor. According to the Research

Consortium of Japan, the median OS survival of the IVA, IVB and

IVC groups of patients was 15.8, 6.1, and 2.8 months respectively [11]. Surgical resection, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or

a combination of different treatment options are used for ATC

patients [8]. The treatment strategy is known as one of the main

factors to predict prognosis [19]. Better survival is seen in cases after total resection of cancer with the combination of radiation

therapy chemotherapy/targeted therapy [12,23,28]. A multimodal approach is particularly recommended for IVA and IVB

stages. Palliative care and clinical trial are more often the treatment of choice for IVC stages [8]. The importance of the surgical

approach was shown in a retrospective review, 1-year survival

is much higher after total resection: 54% patients survived after

total resection of primary cancer, 28% – residual resection and

8 % without surgery [13]. A retrospective study from Finland

showed similar results. The median survival of patients with ATC

was 3.1 months. Longer survival was seen in the radical surgery

group than palliative, 11.6 and 3.2 months respectively. Also,

multimodal approach determined longer median survival (11.8

months) [29]. Historically doxorubicin was the most used agent

in chemotherapy for ATC treatment but new radiosensitizing

agents such as taxanes (paclitaxel or docetaxel), platin, cisplatin, and carboplatin seem to be more effective and can be used

alone or in combination [8]. In addition, these chemotherapy

agents are commonly used with radiation therapy [28]. Results

of molecular studies and the increased use of Tyrosine Kinase

Inhibitor (TKI) therapy are also giving promising results. According to the study of Park et al. 2021, the multimodal approach of

surgery, radiotherapy, and TKI therapy is the most effective and

resulting in a median survival of 34.3 months and in a 6-month

survival rate of 77.8%. Also, it is highlighted that more than half

of the patients showed a good response rate in the group treated only with TKI therapy [30]. Other treatment methods like

thyroid stimulating hormone suppression or radioiodine treatment are ineffective in ATC cases because this cancer does not

produce thyroglobulin and does not uptake iodine. Therefore

there are no tumour markers for ATC [3]. The treatment plan

of patients with ATC is recommended to be managed by a multidisciplinary team of endocrinologists, oncologists, surgeons,

radiotherapists, radiologists and psychologists [3,20]. Moreover

personalized multimodal course of treatment seems to be the

best approach for these patients [21].

Despite the improved prognosis of ATC over the past years

because of target therapy, immunotherapy and combination

of various treatment options, ATC remains a lethal disease

[19,20,28]. It is thought that airway problems and failures of

distant metastases control are one of the main causes of death

for ATC patients [30].

Conclusion

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma is a very rare type of cancer.

Various factors such as metastatic stage, age, socioeconomic

status, treatment possibilities influence the prognosis. Multimodal approach and personalised treatment are recommended

for all anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. There are several clinical

cases of extrathyroidal tumours with anaplastic thyroid carcinoma differentiation. Our presented case represents a very rare

occurrence of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma in the retroperitoneal area. Even though almost 2 years have passed after the

initial diagnosis, the patient is still alive and represents a better

survival than is described in the literature. However, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma is a lethal disease and further studies are

needed for a better management and survival enhancement.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Ethics approval

was obtained and informed consent was gained from the patient.

Consent for publication: Consent for publication was gained

from the patient.

Availability of data and materials: The dataset supporting

the conclusions of this article is included within the article and

its additional files.

Competing interests: Not applicable.

Funding: Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions:

1. Ugne Imbrasaite - Investigation, Writing - original draft,

Visualization, Writing - Review & Editing, Resources.

2. Augustas Beisa - Conceptualization, Writing - Review &

Editing, Supervision.

3. Raminta Luksaite-Lukste - Review & Editing, Imaging analysis description.

4. Dmitrij Seinin - Review & Editing, Imaging analysis description

5. Laurynas Berzanskas - Writing - Review & Editing, Imaging

analysis - Description, Resources.

6. Pranas Serpytis - Review & Editing.

7. Tomas Poskus - Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision.

References

- B Lin ir kt, The incidence and survival analysis for anaplastic thyroid cancer: a SEER database analysis. 9.

- AV Chintakuntlawar RL. Foote JL, Kasperbauer ir KC.Bible Diagnosis and Management of Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer“, Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 2019; 48(1): 269-284. kovo doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2018.10.010.

- E Molinaro ir kt, Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: from clinicopathology to genetics and advanced therapies, Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2017; 13(11): 644-660. lapkr. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.76.

- G Nagaiah A, Hossain CJ, Mooney J, Parmentier, ir SC. Remick, Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer: A Review of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Treatment J. Oncol. 2011; 1-13. doi: 10.1155/2011/542358.

- E. Kebebew FS, Greenspan OH, Clark KA, Woeber A. McMillan Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: Treatment outcome and prognostic factors, Cancer t. 2005; 103(7): 1330-1335. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20936.

- SM Wiseman ir kt. Anaplastic transformation of thyroid cancer: Review of clinical, pathologic, and molecular evidence provides new insights into disease biology and future therapy, Head Neck, t. 2003 25(8): 662-670. 10.1002/hed.10277.

- T R, Liu ir kt. Treatment and Prognosis of Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma: A Clinical Study of 50 Cases PLOS ONE. 2016; 11(10). 0164840. 10.1371/journal.pone.0164840.

- KC Bible. American Thyroid Association Guidelines for Management of Patients with Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer: American Thyroid Association Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer Guidelines Task Force“, Thyroid. 2021; 31(3): 337-386. doi: 10.1089/thy.2020.0944.

- H. Samimi. Molecular mechanisms of long non-coding RNAs in anaplastic thyroid cancer: a systematic review, Cancer Cell Int. 2020; 20(1): 352. doi: 10.1186/s12935-020-01439.

- T Kondo, S Ezzat, SL Asa. Pathogenetic mechanisms in thyroid follicularcell neoplasia, Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006; 6(4): 292-306. 10.1038/nrc1836.

- N Onoda ir kt. Evaluation of the 8th Edition TNM Classification for Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma, Cancers. 2020; 12(3): 552. 10.3390/cancers12030552.

- S Ahmed. Imaging of Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma, Am J. Neuroradiol. 2018; 39(3): 547-551. doi: 10.3174/ajnr. A5487.

- A. Mohebati. Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma: A 25-year SingleInstitution Experience. 2014; 21(5): 1665-1670. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3545-5.

- RI. Haddad. Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma, Version 2. J Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2015; 13(9): 1140-1150. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0139.

- G. Graceffa ir kt. Risk Factors for Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma: A Case Series From a Tertiary Referral Center for Thyroid Surgery and Literature Analysis, Front. 2022; 12: 948033. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.948033.

- X Du. Clinicopathological Characteristics of Mucinous Variant of Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma, Acta Endocrinol. Buchar. 2020; 16(3): 377-378. doi: 10.4183/aeb.2020.377.

- S Togashi ir kt. Thyroid anaplastic carcinoma transformed from papillary carcinoma in extrathyroid area, Auris. Nasus. Larynx, t. 2004; 31(3): 287-292. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2004.03.006.

- Y. Zhou. A New Way Out of the Predicament of Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma from Existing Data Analysis, Front. Endocrinol. 2022; 13: 887906. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.887906.

- A Maniakas. Evaluation of Overall Survival in Patients with Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma. 2000-2019, JAMA Oncol. 2020; 6(9): 1397. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3362.

- S De Leo, M Trevisan, ir L Fugazzola, Recent advances in the management of anaplastic thyroid cancer, Thyroid Res. 2020; 13(1): 17. doi: 10.1186/s13044-020-00091-w.

- M Amaral, RA Afonso, MM Gaspar, CP Reis. Anaplastic thyroid cancer: How far can we go? EXCLI J. 19Doc800 ISSN. 2020; 1611-2156. doi: 10.17179/EXCLI2020-2257.

- T Kelil. Current Concepts in the Molecular Genetics and Management of Thyroid Cancer: An Update for Radiologists, RadioGraphics. 2016; 36(5): 1478-1493. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150206.

- P Kasemsiri ir kt. Survival Benefit of Intervention Treatment in Advanced Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer, Int. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021; 1-8. doi: 10.1155/2021/5545127.

- J Simões-Pereira, R Capitão E. Limbert, ir V. Leite. Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer: Clinical Picture of the Last Two Decades at a Single Oncology Referral Centre and Novel Therapeutic Options, Cancers, t. 2019; 11(8): 1188. rugpj, doi: 10.3390/cancers11081188.

- T Abe. Anaplastic transformation of papillary thyroid carcinoma in multiple lung metastases presenting with a malignant pleural effusion: a case report, J. Med. Case Reports. 2014; 8(1): 460. doi: 10.1186/17521947-8-460.

- A Deeken-Draisey, GY. Yang, J Gao, BA Alexiev. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: an epidemiologic, histologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular single-institution study, Hum. Pathol. 2018; 82: 140-148. gruodž. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2018.07.027.

- ME Cabanillas, DG. McFadden, ir C. Durante.Thyroid cancer, The Lancet. 388, nr. 2016; 10061: 2783-2795. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30172-6.

- N Huang. An Update of the Appropriate Treatment Strategies in Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer: A Population-Based Study of 735 Patients, Int. J. Endocrinol. 2019; 1-7 doi: 10.1155/2019/8428547.

- P Siironen. Anaplastic and Poorly Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma: Therapeutic Strategies and Treatment Outcome of 52 Consecutive Patients, Oncology t. 2010; 79(5-6): 400-408. doi: 10.1159/000322640.

- J Park. Multimodal treatments and outcomes for anaplastic thyroid cancer before and after tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy: a real-world experience, Eur J. Endocrinol. 2010; 184(6): 837-845. doi: 10.1530/EJE-20-1482.

- A Nourparvar, J Lechago, GD. Braunstein. Thyroid Carcinoma Arising from a Sacrococcygeal Mass: A Malignant Teratoma? Thyroid. 2004; 14(7): 548-552. liep., doi: 10.1089/1050725041517101.

- KH Lim, KW Lee, JH Kim, SY Park, SH Choi, JS Lee. Thyroid Carcinoma Initially Presented with Abdominal Cutaneous Mass and Hyperthyroidism, Korean J. Intern. 2010; 25(4): 450. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2010.25.4.450.

- JP Solomon, F Wen, LJ Jih. Anaplastic Transformation of Papillary Thyroid Cancer in the Retroperitoneum, Case Rep. 2015. 1-4. doi: 10.1155/2015/241308.